Musings on Writing & Publishing

Why Are Publishers Happy About Missing Out on the Digital Revolution?

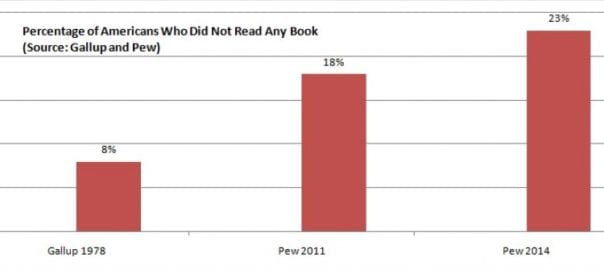

The chart you see above is from Gallup and Pew measuring the percentage of adults in the U.S. who have not read a single book in the year measured.

It was 8% in 1978 and has been hovering at 23-27% in recent years. This is not a trend one associates with a growth industry. Meanwhile, I see newspaper editors, authors, and book publishers celebrating the death of the ebook without looking at this long-term trend of reading decline. Are they dancing on their own graves?

It seems likely that print book reading has been in decline since around the time the Internet came on the scene because of new entertainment choices. We know from many studies that people are spending more and more time engaged with content provided on a networked screen: Netflix, Amazon Prime, Facebook, Instagram, streaming sports, and so on.

Yet in the traditional book publishing industry, the collective decision was made to raise ebook prices to about what paperbacks sell for to save the old industry. And in the process kill the only networked screen innovation the book industry could participate in, the digital book for Smartphone and tablet reading. Vested interests across the supply chain published stories about the inferiority of reading books on a screen. How people remember less when reading digitally. An active campaign was undertaken to ward off innovation by The Establishment. (Them again!)

The inclination in the face of change is to duck one’s head in the sand and hope you can make it though the storm. Maybe YOU can make it, but what about future generations who want a viable book industry? This is analogous to the old wooden ship builders deciding not to enter the iron age. Or the suits at Kodak who smugly looked at industry-funded Photo Marketing Association research, ignoring what was happening in the larger world. Just as with AAP research, the photo industry research ignored the emerging players and their market growth quietly occurring outside the normal competitive landscape. Do you remember when supermarkets sold food but didn’t make it available to eat in the store? Someone smart decided competition was happening all around them at restaurants so along came Whole Foods, where people now eat right next to where others pay. Brilliant!

We know from looking at traditional publishing financial results that publishers gave up easy profits when they chose to ignore the future of the ebook and hide in the print past. The only way the old business models have survived is through continued consolidation, which means pumping through more titles in lower volumes to fewer readers to just about stay even. For now. When the next recession comes, that will change again. Those higher number of titles coming from fewer traditional publishers with less staff has to translate into a poorer experience for authors as a byproduct.

Crossing the chasm from the old, which provides most of the current income, to the new is nearly impossible. This is why competition almost always comes from the outside, from new players who have no investment in the old ways so are free to seize opportunities while the old plays a difficult balancing game. I experienced this firsthand when the 35mm photo industry had huge investments in obsolescent technology and equipment, while needing to also invest in the digital new, the sum being a very expensive, unsustainable business model, which was too much weight for the likes of Sony, Konica, Kodak, and Polaroid.

The publishing industry seems to have throttled back the digital new more than was needed. No one I speak with in the book industry can answer the important question: “How many sales did you lose when you raised your ebook prices to the same as paperback?” If you apply the strategic thinking of dividing customers into clusters of Most Engaged, Somewhat Engaged, and Not Engaged, I would expect many in the Somewhat Engaged group bought fewer books once ebook prices went up to the current high (I would say absurd) levels. Yes, the Most Engaged are stepping up as they always will in continuing to support the old print business and indie booksellers, but can publishers survive well into the digital future in a highly competitive screen-based entertainment marketplace with just the Most Engaged? I doubt it.

A possible better way to straddle the change would be to launch the hardcover edition that all publishers currently offer for those Most Engaged customers, and hold off on both the ebook and paperback editions until a year later when released simultaneously. Price the ebook at $9.95 intended for the Somewhat Engaged shoppers. The $16-$20 paperback sales should not be hurt much by this change, as those who prefer to read in paperback will pay $10 more. And the net margins should be higher, without returns and printing costs. Bookstore sales should stay flat, especially when Barnes & Noble is out of the mix. The smart indie booksellers can do well in this overall environment that allows publishers to play a new game, as well as an old one.

I hear authors and industry insiders blaming Amazon for lowering book prices and reducing everyone’s profits as a result. (Same thing they said about Barnes & Noble back in 1986.) They claim this is now (ironically) why Barnes & Noble is on the ropes. I disagree. Barnes & Noble is on the ropes because they are caught in the middle, too large to compete with indie bookstores and too small to compete with Amazon. The core issue is not Amazon and lower book prices, but an overall shrinking market for book reading. That is the challenge people should be focusing on, not whining about how the shrinking pie is being affected by unfair competition. Ebooks were that path forward, as a new competition for other forms of digital entertainment, but pricing ebooks at $14.95 will never attract those less engaged potential book buyers. Duck and cover is not a winnable long-term strategy. You can’t go home again. You can be progressive or regressive.

It’s the same old question: do you see digital as a threat or an opportunity? It is in fact both, so don’t forget about the opportunities.

Missing out on the digital revolution is not an option for book publishers who want to operate well into the future. Actively promoting and celebrating the decline of the one new good thing that has come along to make the industry competitive with all other entertainment options, strikes me as self-defeating strategy.